CONVERSATIONS / MOUSSE MAGAZINE

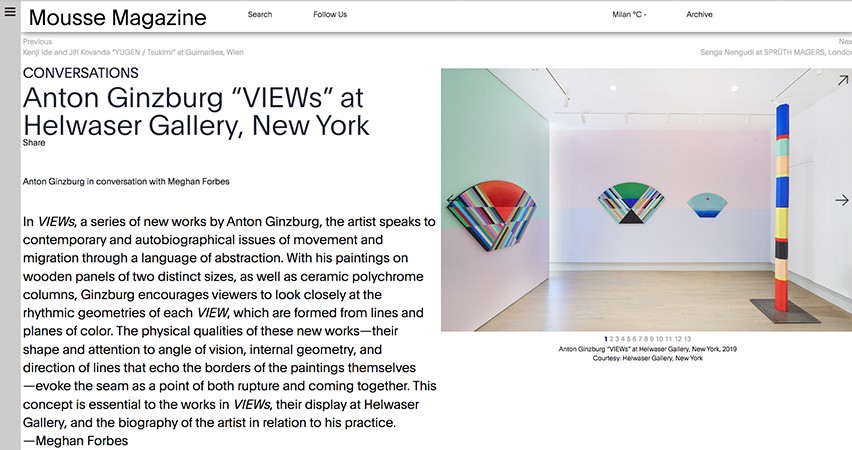

Anton Ginzburg “VIEWs” at Helwaser Gallery, New York

Anton Ginzburg in conversation with Meghan Forbes

http://moussemagazine.it/meghan-forbes-anton-ginzburgs-views-at-helwaser-gallery-new-york-2019/

In VIEWs, a series of new works by Anton Ginzburg, the artist speaks to contemporary and autobiographical issues of movement and migration through a language of abstraction. With his paintings on wooden panels of two distinct sizes, as well as ceramic polychrome columns, Ginzburg encourages viewers to look closely at the rhythmic geometries of each VIEW, which are formed from lines and planes of color. The physical qualities of these new works—their shape and attention to angle of vision, internal geometry, and direction of lines that echo the borders of the paintings themselves—evoke the seam as a point of both rupture and coming together. This concept is essential to the works in VIEWs, their display at Helwaser Gallery, and the biography of the artist in relation to his practice.

—Meghan Forbes

MEGHAN FORBES: Let’s start with the legacy of the twentieth-century Russian avant-garde in your work, as well as the relation of your work to more contemporary global art production. With whom do you see yourself in conversation, at least in this particular body of work?

ANTON GINZBURG: This body of work started with the 2013 video experiment Color and Line, which is included in this show. I was interested in the Constructivist pedagogy and its Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg) branch (GINKhUK, or the State Institute of Artistic Culture) in particular. My research focused on the exploration of color, its interaction with the spatial environment, and the incorporation of these principles into the objects of observation. It was achieved through techniques of “expanded vision” or zorved (vision + cognition), which created the understanding of interconnections as a “fusion of essences but not of semblances,” to quote Mikhail Matyushin.[1] I was also studying the text “Theory of Vision” (1958) by Władysław Strzemiński, a Polish artist who was also a student at VkHUTEMAS[2] at the time.

MF: The flat screen with the video you refer to is leaning against a mural in the back of the space. How do you see this work in relation to the gallery setting?

AG: In this video I wanted to engage the formal vocabulary of the modernists while also deconstructing it, as sort of a DIY approach to Suprematist pathos. I took the methodologies found in the artists’ texts and tried to apply them to a very mundane situation. The film was shot in the laundry room of Bard College; it shows a continuous sequence of color compositions created with pieces of fabric, in between structural “cuts to black.”

MF: It also evokes this idea of the seam, which is so central to your work. The cut in the video—which is created manually by turning the light switch on and off—is also evoked in the paintings themselves, where two colors meet, where two new shapes are formed. I wonder if you could talk a bit about the concept of the seam as a place of convergence, but also a place where things split, in relation to your own biography, for instance the way you see your own hybrid identity as a Russian-born American artist.

AG: Yes, I think that a seam or a joint in an artwork, whether it is a painting, film, or sculpture, is a record of where a decision was made. It’s where materials, ideas, and histories meet, and it has to be acknowledged formally and conceptually—the detail that really reveals formal thinking. VIEWs is based around that concept. It traces the moment when the viewer encounters the artwork. The paintings themselves are diagrammatic representations of human binocular vision that are made up of planes and lines. They propose and define the choreography of moving through the exhibition space. Additional shifts are achieved through vertical movements, and through suggested horizon lines painted on the walls.

MF: It’s almost like a set of instructions for the viewer as they navigate the space. We were talking earlier about exhibition versus installation. Can you say how you envisioned this particular exhibition being installed in this specific space? How did you think about activating and instructing the viewer by constructing a sort of choreography, especially with the polychrome columns in the other room?

AG: VIEWs is built around the notion of fragmentation of the viewing experience, an experiment in reduction. In the exhibition I propose a number of viewing points and introduce sculptural objects that create awareness of the human scale of being in the space. The mural in the second room echoes the columns as a geometric representation on the wall.

MF: I really like the rationalization of this process, but at the same time there’s this moment of chaos introduced by the refracted mirror within the mural. As much as you can conceive of our relationship to these objects in space, it’s sort of randomized or broken up based on our situation within the room. As I was saying earlier, we might catch a view of a painting in the other room, we might catch a view of the street. At the same time, we have this video work below. I wonder if you could speak more to this element of chance—especially as it relates to this playful moment in the exhibition. I don’t know if it’s something you thought of, but it struck me—it’s not really selfie-friendly. But it gestures toward this looking at yourself through the work. Could you extend that back to the columns in the other room—their physical placement in the space and how they give us a set of instructions for how to move around them?

AG: When I was working on the exhibition, I was thinking about a system of objects and images, their relationships, and the actions that pass onto the painting as an object as it transitions into new contexts. The exhibition is modular in the way I defined pairings of painting with sculpture and with murals or video, but these placements are also interchangeable. As you walk through the exhibition, porcelain columns serve as an initial framing device. Depending on one’s position, they interact with the murals behind them. Some of the colors disappear because they match some of the sculptures’ color glazes, functioning as building blocks of colors.

MF: Do you see this as an installation, where the viewer is activating the space and participating in the work? Or do you consider it more an exhibition? We have paintings hanging on walls, but then the walls themselves are painted. You’re playing with this threshold between installation and exhibition.

AG: I think my position is not definitive. I want it to be modular, working both as an exhibition and as a fragmented installation. I’m interested in the diagrammatic nature of the painting where the subject becomes the action that moves onto the object. It visualizes the behavior of objects within different systems and environments.

MF: Both Strzemiński and Kobro[3] were thinking very deeply through the idea of Unism4 of their work and its political and social capacity as well as its capacity as an abstract work of art. In a lot of our conversations, we move between talking about the painterly quality of the work, the space it takes up in the room, and its relationship to your biography. Would you be willing to formulate a politics of abstraction in these works, or verbalize how they reference outward to the larger sociopolitical place in which we find ourselves? In which you find yourself?

AG: Abstraction is something that keeps changing and returning. What abstraction meant in the twentieth century—the modernist concept—is quite different from what we have now. The modernist vocabulary and methodology have been established, but their meanings and our historical relationship to them have changed. I was interested to test how it all functions in relation to the current North American context. However, unlike the modernists, I am not searching for some pure, ideal form. Form in my work is always dynamic. It develops through interaction with the surrounding context, with history, with material properties of things, and with whatever else might shape it. I see my work as an analytical system for observing the process of the development of form as it undergoes semantic, material, and historical transformations.

.......

[1] Mikhail Matyushin was a Russian painter and composer, and one of the key figures of the Russian historical avant-garde. He developed theories of viewing and founded the Visiology Center (ZorVed), which researched human perceptive abilities, including vision.

[2] The VkHUTEMAS was the Russian state art and technical school, founded in 1920 in Moscow. Many of the key leaders of the Russian historical avant-garde movement were associated with the VkHUTEMAS.

[3] Katarzyna Kobro (1898–1951) was a leading Constructivist sculptor, and one of the key Eastern European avant-garde artists. She was also Strzemiński’s wife.

[4] Unism is a theory that Strzemiński and Kobro developed. Unism insists upon the organicity of an artwork. In his writing on Unism, Strzemiński wrote that “The law of organic painting requires: the greatest possible union of forms with the plane of the picture.” This stance differed from that of Constructivism, which maintained that art had to serve social utilitarian uses. See: https://post.at.moma.org/content_items/1150-wladyslaw-strzeminski-s-theory-of-vision

......

Meghan Forbes is a postdoctoral fellow in the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is also a visiting scholar at the Institute for Public Knowledge at NYU. Forbes was previously the C-MAP (Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives) Fellow for Central and Eastern Europe at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She is the sole editor of International Perspectives on Publishing Platforms: Image, Object, Text (Routledge, 2019), and in Fall 2018 she cocurated the exhibition BAUHAUS↔VKhUTEMAS: Intersecting Parallels, in the MoMA Library. Forbes has published her essays, reviews, and translations in venues such as Hyperallergic, Literary Hub, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Words Without Borders, and the Michigan Quarterly Review, and is the founder and co-editor of harlequin creature, an arts and literary imprint.