Seaharp, 2014

Plaster, cement, wood, paint, piano wire and piano pins, computer, camera, speakers

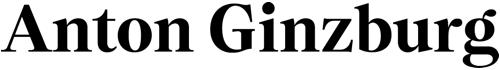

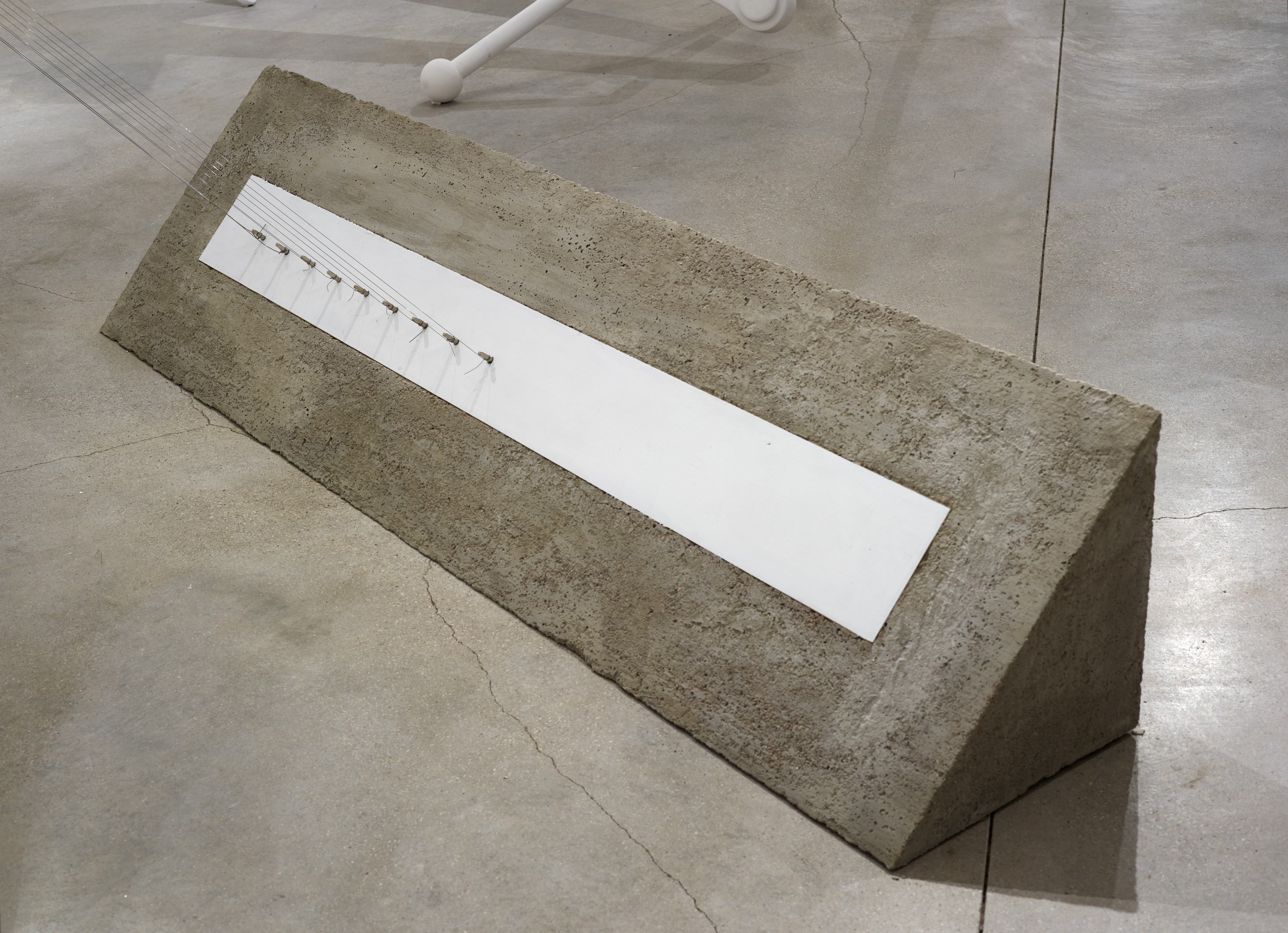

The interactive sculpture Seaharp, composed of a large group of objects: a relief-encrusted wall diagonally inserted into a corner of the room; two triangular concrete wedges set at right angles to one another; a life-size plaster cast of an anchor; metal strings drawn between points on the wall to the wedges and anchor; and a petrified seashell. The anchor and seashell represent residue from the dried-up sea that Ginzburg photographed during his walk. The wedges introduce other regional references: according to the artist, they are modeled after large marble Koran stands in Uzbekistan; they also recall the concrete remains of the military buildings scattered across the sea basin that have since become scavenging grounds for builders. The same triangulated wedge, or prism, shape reappears as a plaster cast applied serially to the wall to form three long horizontal reliefs whose protruding edges create a modulated, rhythmic pattern of light and shadow.

Metal wires connecting these disparate elements transform the whole into a monumental musical instrument. Invoking the sonic quality of the dry Aral Sea basin, Seaharp is an acoustic environment responsive to the viewer’s movement. Like a re-imagined Aeolian harp, Seaharp emits sounds that Ginzburg recorded throughout his journey. But while an Aeolian harp traditionally relies on the wind to caress its strings and trigger musical notes, here the motion-induced sound is the whistling of the wind across the landscape, albeit digitally recorded and electronically processed for presentation in the gallery.

As a corner relief, Seaharp pays formal homage to the pioneering Russian avant-garde artist Vladimir Tatlin, whose corner counter-reliefs ushered in a new era in Russian art by anticipating the Constructivist dictum of the integration of art and life in the service of a modern communist state. In Seaharp, Ginzburg moves the concept of Tatlin’s constructions—which were indebted to the Orthodox corner placement of icons—from the walls onto the floor. The tunes issued by this life-size walk-in corner sculpture amount to a wistful serenade for a failed utopian aspiration, whose hopeful trajectory remains as unrealized as Tatlin’s 1919–20 Monument to the Third International.